Understanding community resilience as the ability of a community to make use of available resources (such as energy and food) to respond and recuperate from shocks (e.g. economic crises and global pandemics)[1], we can say that resilient communities are the ones who mitigate adverse situations, and are able to return to their normalities, stronger.

And what if a community’s normality is full of adversities?

The LGBTQ+ community has what I call historical resilience. Apart from enduring with the whole world global pandemics and economic crises, like the Spanish Flu in the early 1920s, the 2008 financial crisis and most recently, Covid-19, the LGBTQ+ community has also gone through the AIDS pandemic, as well as a long-lasting “relationship” with prejudice, discrimination and invisibility. In this way,

“LGBTQ+ people have had to learn how to exist while resisting, how to live while dying, how to laugh while crying, in other words, how to be resilient 100% of the time”.[2]

Around the globe, LGBTQ+ populations have made innovative pathways to resist daily prejudice and express their true selves. Being banned from most places pushed them to create their own spaces. Cities offer the LGBTQ+ people higher possibilities to get together in grassroots organisations, night-time spaces, shelters and other LGBTQ+ spaces where a social network can be developed due to its tolerance, diversity and openness to new experiences. Not only do these places let them explore their potentialities through art, music, dance and fashion, they also create a ‘sense of community’ that makes it possible for people to take action in favour of the most vulnerable in our society.

Shelters of resilience!

The idea of an LGBTQ+ space goes beyond the common spaces of entertainment like clubs and bars. In a survey I conducted with over 200 respondents in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, the positive social impact of spaces like the LGBTQ+ shelters was emphasised; LGBTQ+ spaces “take back” the right to occupy, to exist and to experience the city. My research showed that all LGBTQ+ spaces in Rio play a multifunctional role due to the existing discrimination towards queer bodies. Brazilian cities, like many others worldwide, have never reached a high-level of acceptance towards their LGBTQ+ populations. This fact stopped neoliberalism from co-opting these highly-political, yet commercial to some extent, spaces and draining them of their social value.

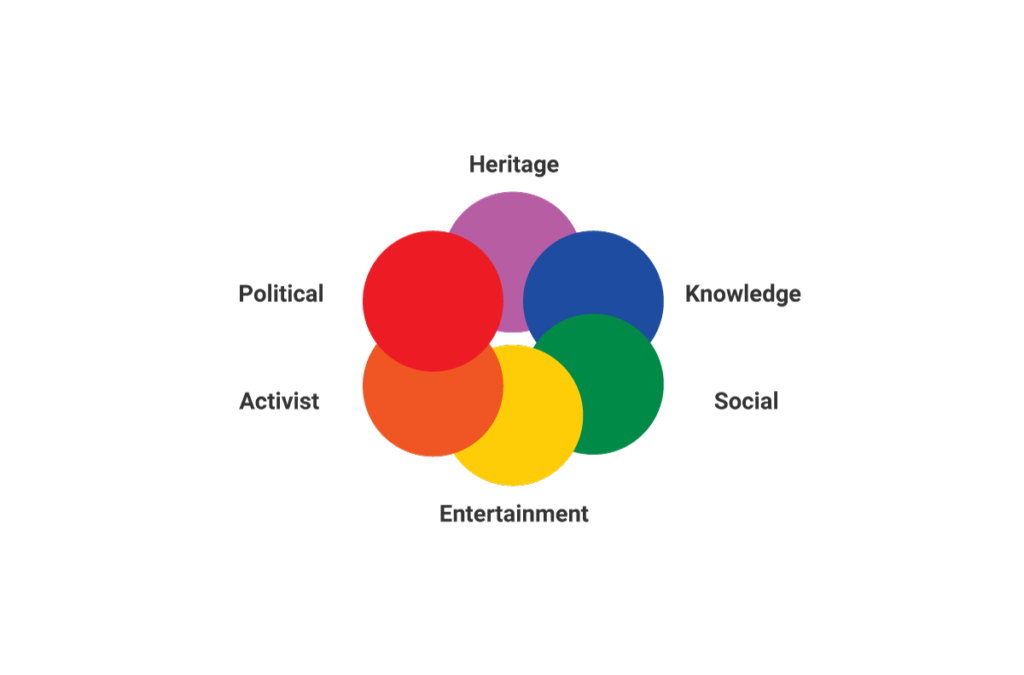

The following model [figure below] has been created to demonstrate intersecting functionalities that can be applied to the Brazilian context – and to others, to a certain extent. In other words, as long as queer bodies are contested in the Global South’s cities, even purely entertainment LGBTQ+ spaces – such as nightclubs and bars – embed a political, social, activist and cultural potentiality.

The level of each function differs according to the core purpose of each space. For instance, in a shelter, the level of entertainment is smaller than in a nightclub or a bar, but the political and activism levels are much higher.

“Brazilian LGBTQ+ spaces would be defined as a place where intersections of functionalities meet regardless of their economic – or lack thereof – purposes”.[3]

Rio de Janeiro, a Not-So-Marvellous City for LGBTQ+ People

In Rio de Janeiro, as well as in most global cities, the LGBTQ+ community, are still carriers of a “social stigma resulting from a degenerative process of cultural labeling”[4], creating spaces of sociability and a distinctive culture. In LGBTQ+ urban spaces, the LGBTQ+ community organises itself for political acts and claiming purposes.[5] Rio, due to its diversity and international recognition through Carnival, was able to create a locus for many marginalised groups compared to most Brazilian cities; therefore, being considered a liberal environment.[6] However, with the HIV epidemic in the ‘80s, which especially stigmatised this community, what was being constructed through sexual (homo) liberation movements, was repressed by conservative values. Consequently, despite branding itself as a “libertarian and diverse city”, Rio de Janeiro also has a well established repression movement that is averse to these new “freedoms”.[7]

Therefore, the format of queer urban spaces, like the ‘LGBTQ+ shelters’, becomes fundamental for queer people’s realities as the breakdown of family ties is much greater for this group. A survey carried out in 2016 in the city of São Paulo found that 8.9% of the street population identified themselves as LGBTQ+; these people were eight times more likely to be victims of sexual abuse on the streets compared to people who self-identified as both heterosexual and cisgender.[8] The potential for resistance to the current Brazilian context – marked by extreme violence, marginalisation and censorship of queer culture – that these shelters represent is infinite. This is because these experiences together allow for the production of knowledge, culture, art, politics, and activism that help to neutralise the gloom that the country is going through. In addition to being a support and security group where subjects can perform their subjectivities in a freer and more authentic way. Some examples of such houses in Brazil, in order to illustrate and bring greater knowledge of these spaces that constantly need help to function, are: Casa 1[9] – São Paulo, SP; Casa Nem[10] – Rio de Janeiro, RJ; Casa Transvest[11] – Belo Horizonte, MG; and, Abrigo Trans da Atransce[12] – Fortaleza, CE.

Advocating for a resilient Queer urban future

When this pandemic is finally over, cities must think in and look after those whose lives continue to face constant challenges, like the LGBTQ+ population. Cities need spaces where races, classes, genders and sexualities cross. Spaces that are plural, diverse, creative, political, social and activist. Spaces free from the chains of heteronormativity and cisnormativity. Simply put, cities need more Queer urban spaces for the resilience of the (LGBTQ+) community.

Extended version of the article “Queer Reflections on Community Resilience.”